“What if we tried (insert half-baked idea with buzzword du jour)?”

“Hmm, that’s interesting, what if (insert self-serving non-sequitur) instead?”

Having sat through countless growth meetings, I’ve over the years noticed that most ideas seem to fall in the ‘silver bullet’ category, some revolutionary idea that’ll save the company (this is as opposed to other methods of operational improvement, such as variance reduction). And in almost every case, these silver bullets were fondly received by many colleagues because it abides by the culture of ‘failing fast’.

My experience isn’t unique, ‘failing fast’ is an extremely popular mantra that’s long been echoed in the VC-backed startups chamber. While the saying may have had practical beginnings, at this point, through a decades-long game of telephone it means different things depending on the day and the person you ask. Furthermore, I argue it’s one of the main operational reasons behind the tech startup layoffs.

Two common interpretations of this mantra prove especially problematic.

- Testing ill-researched, gut-feeling ideas

- Labeling inconclusive results as failures for the sake of ‘speed’

In all both scenarios, the issue manifests as improper resource allocation.

Testing Ill-Researched Gut-Feeling Ideas

During my time on the B2B expansion team at a telecom startup, I was tasked with designing a pricing model for the expansion team in the handful of different markets we’d already launched.

We were the team responsible for network expansion in different markets through purchasing commercial leases on viable sites to place our equipment. The project was catalyzed by the wildly varying penetration rates for each market when using the current one-size fits all pricing model.

Since the technology was line of sight based, the pricing model that had been in use was an ad-hoc model based on physical characteristics of a given site. Generally, the taller the site, the bigger the area of reach, and the higher the acquisition budget.

However, as multiple markets launched, there were constraints and new variables coming into play, such as the commercial property owner’s threshold on for drafting any lease, even if it’s nearly unusable by any other tenant (5×5 space on a rooftop), or how high is too high for the equipment to reliably cover a given area? Or how much average foliage is there leading to partial obstruction affecting signal strength? Or how much average rainfall was there in a year leading to rain-fade of signal strength?

I translated everything I learned from resident subject matter experts into a few dozen quantifiable variables and ran regression analysis to come up with a pricing model. The final product was a market-adjusted pricing calculator with 13 different inputs, the data for which was readily available for each site from census info, historical weather patterns, topological GIS data, and historical real estate prices.

The first pushback I received from the team was how market adjustments led to up to a 125% price difference in similar sites in different markets.

Santa Clara, CA had a market adjustment term of 2.25 vs. the baseline of 1.00 in San Leandro for average sites. This meant Santa Clara sites need to budget 2.25 times the base rate to achieve similar acquisition rates, this also meant that COGS was significantly higher in Santa Clara than the baseline markets. While I got approval for the new pricing for the sake of expansion, given we couldn’t charge radically different prices for internet service in the same metro, a 125% premium in COGS was very problematic for profitability.

So why did we enter these markets in the first place? Unit economics is presumably something every business needs to consider, was there insufficient due diligence? The short answer is yes.

There were so many ways this could have been avoided, a market survey through field ops which would have taken a few days, or even the crudest viability models from the engineering team at the cost of a few dozen engineering hours would have indicated that at least half these markets were bad fits for the business model.

We ended up pulling out of Santa Clara.

I ran across this ‘premature market launch’ issue at 2 of the 3 other startups where I’ve held tenure, both also to bad results. Most recently, at a late-stage startup, we pulled out of multiple markets at the cost of $1.3m+ per market, again due to lack of proper due diligence.

So why does this happen?

I argue it’s due to prolonged periods of cheap capital (gone now) and frequent conflation of ‘fail-fast’ with ‘bias toward action’. The former giving unprecedented room for experimentation if there was speed and the latter speciously concluding that planning is inaction, leading to its de-prioritization.

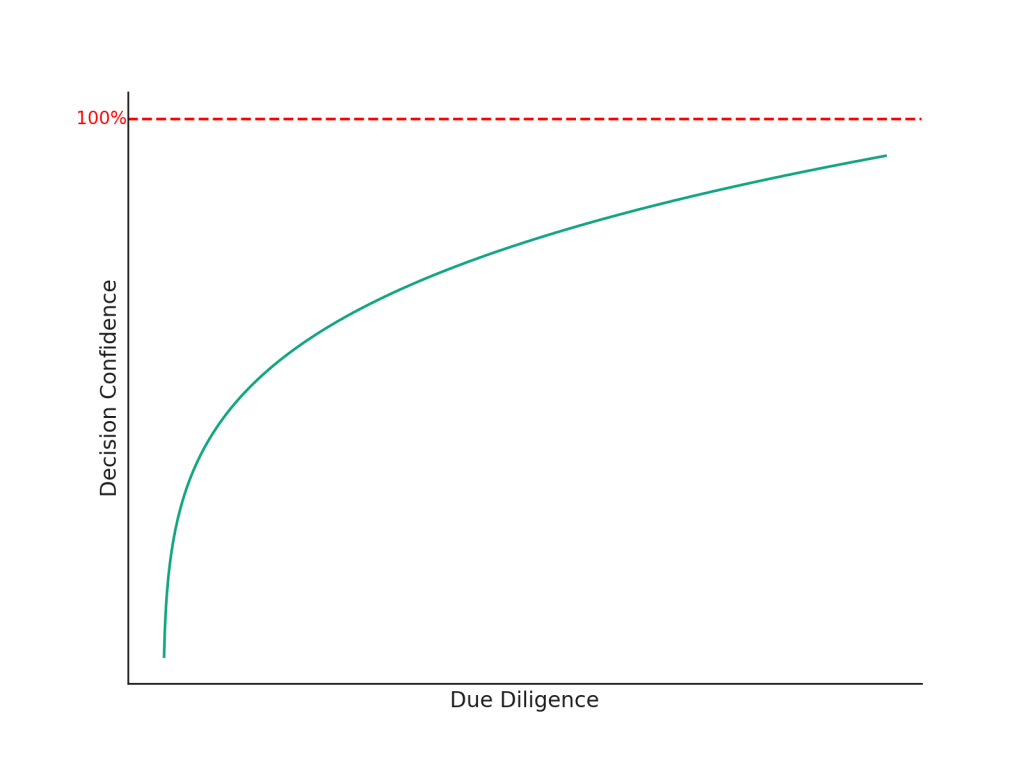

The figure below describes the general relationship between due diligence resource intensity and decision confidence. It’s a graphic representation of the principle “we become more confident in the decision made after we spend more time in the research phase”.

But each business decision is different, how does an organization approach the minimum required confidence in a pragmatic way? How does a given decision’s curve look different? What are the discrete data points which make up the curve? How do we identify these points? What are the boundary conditions?

In addition, the curve above looks similar (but not the same) for confidence in whether an idea works post-launch of testing. And overlooking the nuances can be problematic. What are these nuances?

I cover all these questions in part 3.

Next, in part 2, I dive into what can go wrong under the ‘fail fast’ mantra when a testing an idea is already underway looking back on the time when executive impatience extinguished the last chance we had at a company.

Leave a comment